Friend or Faux?

The AI necklace campaign that took over NYC—and why it hit a nerve in fashion culture

It began without warning. A stark white poster appeared in Manhattan’s subway stations featuring a small, sleek pendant and a single word in lowercase: friend. No logo, no tagline, no QR code. Just the image of a futuristic accessory hanging mid-air—minimalist, mysterious, and undeniably intentional.

Within 48 hours, the ads were everywhere. Over 11,000 subway cards, 1,000 platform posters, and more than 100 urban panels had been overtaken by the same visual: a small, chrome object and that five-letter word. It looked more like a campaign from a conceptual fashion house than a tech startup.

And then, New York responded.

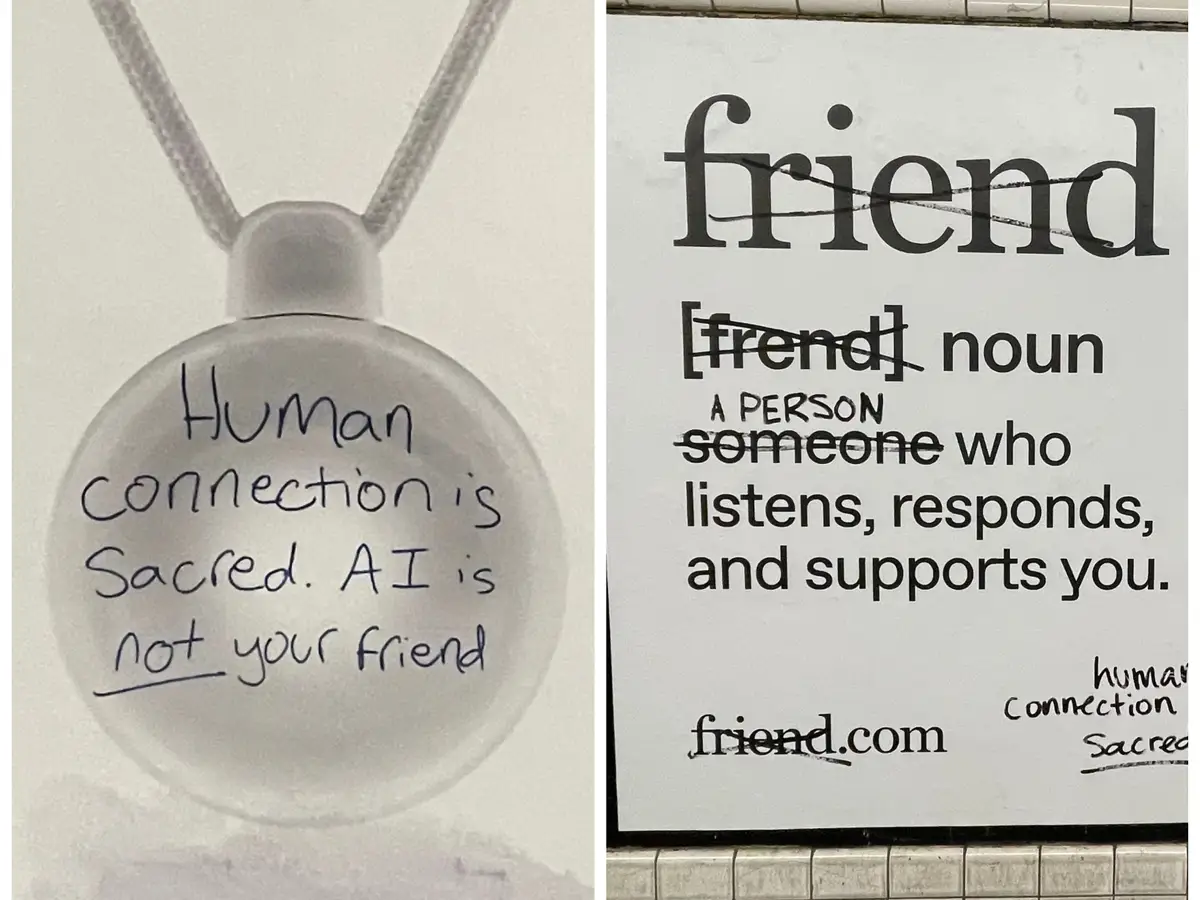

Posters were defaced with Sharpie, paint, and stickers. Messages appeared: “AI doesn’t care about you”, “Make real friends”, “Surveillance disguised as jewelry.” What began as a hyper-controlled aesthetic rollout became a city-wide conversation—angry, ironic, raw.

The product behind the campaign? A wearable AI called Friend, designed to be worn around the neck like a necklace. It listens to conversations, learns from its environment, and sends texts to its user through an app. Described as an “AI companion,” it promises connection, understanding, and emotional presence.

But it also raises questions—ones that go beyond tech and into the world of fashion, identity, and how people choose to present themselves.

Friend is not the first AI wearable, but it’s possibly the first to market itself through fashion rather than function. The pendant is polished, geometric, and unobtrusive—more sculptural than digital. With no visible branding, no lights, no interface, it fits seamlessly into the fashion landscape of 2025: quiet luxury meets emotional technology.

Courtesy of TheAIGRID

It’s easy to imagine Friend layered with silver chains over a Margiela knit, or peeking from under the collar of an oversized leather jacket. It pairs more with Balenciaga than with Best Buy. This wasn’t a piece of consumer electronics—it was a statement piece, even if its statement was left unsaid.

But that silence didn’t last long. The aesthetic restraint of the campaign—its deliberate lack of context—only amplified the public’s emotional reaction. Unlike traditional product launches that overwhelm with features, Friend chose subtlety. In New York, a city hyper-literate in both art and advertising, the result was a kind of visual whiplash. People didn’t just see the posters—they answered them.

That backlash didn’t appear to surprise Avi Schiffmann, Friend’s 22-year-old founder. In interviews, he suggested the ad space was intentionally “left blank” for interpretation. The vandalism was reframed as part of the campaign, a kind of user-generated critique. What others saw as defacement, the company treated as engagement. Friend wasn’t just asking to be worn—it was asking to be talked about.

And it was. But not all press is good press—especially when the product in question positions itself as emotionally intelligent.

The problem many saw wasn’t the pendant’s function, but its implication. Friend suggests a future where companionship is worn, programmed, and processed. A future where conversations are harvested into data, intimacy becomes a UI feature, and loneliness can be monetized at $49 per necklace.

To some, that feels dystopian. To others, simply honest.

What made the campaign powerful—its minimalist design, its almost clinical confidence—is the same thing that made it feel emotionally vacant. The pendant might be styled like high fashion, but it asks to play a deeply human role. That tension is where discomfort begins.

In the world of fashion, wearables have always carried meaning. A ring can signal relationship status. A hoodie can signal subculture. A handbag can say more than a LinkedIn profile. Friend isn’t just trying to be wearable tech—it’s trying to become a social symbol, one that suggests emotional availability, tech fluency, and aesthetic restraint.

Courtesy of Business Insider

But what happens when that symbol becomes controversial?

In defacing the posters, New Yorkers added something back to the campaign that wasn’t originally there: feeling. Whether through mockery, poetry, or protest, the graffiti became part of the story. It exposed a collective anxiety about the line between human and artificial, connection and performance. And it reminded onlookers that even the most minimal design can carry a complicated message.

As Friend eyes wider adoption, and as AI continues to blend into lifestyle and fashion, the industry will likely see more of this overlap. Wearables won’t just count steps—they’ll claim to understand emotions. Accessories will become interfaces. Outfits will start responding.

For now, Friend exists in a strange space: half product, half provocation. It might not be the future of fashion, but it’s a glimpse into one possible version of it—a version where the line between self-expression and self-surveillance is defined by what hangs around the neck.

And that, more than any ad, is what’s worth talking about.

Featured Image: Courtesy of Fortune